By Chris Ross, Executive Professor, C.T. Bauer College of Business

In the early days of 2017, it behooves oil and gas companies to reflect on the past, while making plans robust to an uncertain future outlook. There are several questions that should be asked:

- Where are we in the oil and gas price cycles?

- How will politics and policies affect the business outlook?

- What are the appropriate strategies?

Learning from the Past

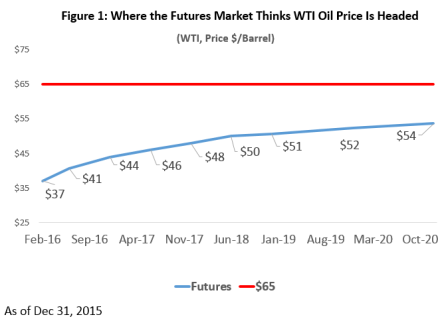

It will not surprise any investor in oil and gas and related businesses that theirs is a cyclical business. Prices run up when supplies fall short of demand, hover on the summit for a few years, then tumble as new supply sources are developed and demand growth slows down (Figure 1).

After the collapse of 1986, oil prices remained volatile through 1990, then declined further through 1998 as production from the Middle East, Norway, Iran and Venezuela increased to meet demand growth and replace declines in Russia and North America. One consequence of the price decline in 1998 was major oil company mega-mergers. These resulted in high-grading of projects, reduction in aggregate capital spending and slowdown in production increases, setting the stage for the run-up in prices after 2002.

The period from 1986 through 2002 can be seen in retrospect to have been a “long grind,” as oil prices were set by the long-term marginal costs of incremental production sources needed to satisfy demand growth and replace declining production from mature oil fields and political turmoil.

Tightly controlled wellhead natural gas prices in the 1970s led to supply shortages. The 1978 Natural Gas Policy Act (NGPA) started a process of decontrol and broadened the responsibility the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission held over the industry.

In 1985, FERC issued Order No. 436, which changed how interstate pipelines were regulated. This established a voluntary framework under which interstate pipelines could act solely as transporters of natural gas, rather than filling the role of a natural gas merchant. However, it wasn’t until Congress passed the Natural Gas Wellhead Decontrol Act (NGWDA) in 1989 that complete deregulation of wellhead prices was enabled. Issued in 1992, FERC Order No. 636 completed the final steps towards a competitive market by making pipeline unbundling obligatory.

Natural gas became a traded commodity subject to its own cycles (Figure 2).

The decontrolled market opened new sources of supply, enabled by new seismic technologies that uncovered large resources of natural gas under the Gulf of Mexico (GoM) continental shelf. A gas bubble was inflated, holding spot prices below $3/million British Thermal Units from 1989-1999. New markets, notably independently owned cogeneration plants empowered to sell electricity to industrial plants and the grid at prices representing the “avoided cost” that new utility projects would have incurred, caused rapid demand growth. The bubble burst as gas production in the Gulf of Mexico peaked, natural gas prices increased and LNG import terminals were built.

Higher prices induced innovation on the supply side as George Mitchell figured out how to extract natural gas from tight shale rock, and the technologies were deployed in other gas and then oil shale plays. Natural gas prices collapsed in 2009: demand accelerated as natural gas displaced coal in the power sector, somewhat constrained by limitations on pipeline transportation. New pipeline connections were built despite opposition; LNG import facilities were converted to export facilities.

Mark Twain wrote “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” If history were to repeat itself, oil prices would remain low for another “long grind”, mirroring 1986-2002 by declining further over the next 15 years; natural gas prices would start strengthening in 2019.

Politics and Policies

For oil markets, turmoil in the Middle East and Africa withdrew about 3 million barrels per day from world markets between 2005 and 2015. Ideological conflicts, coupled with the demographic realities of a growing number of young men with few employment opportunities, suggest continued instability.

OPEC’s agreement to reduce production with apparent support from Russia will be tested by inducing expansion of U.S. shale production. But the need for cash to meet social commitments is likely to reduce funding available for capital spending by the national oil companies and will lead to lower production, regardless of the OPEC quotas. The “long grind” seems likely to be shorter this time around, more likely five rather than 15 years.

The past eight years have seen a series of rules designed to suppress coal use, to the benefit of natural gas as well as renewables. Several of these rules are still being litigated, and the new administration may choose not to defend constitutional challenges by various individual states. There may also be a reduction in subsidies and mandates favoring renewables, but natural gas will likely find it difficult to displace coal at the pace seen in recent years. LNG exports will allow further production growth, but the resource available in shale plays in 2017 is significantly larger than the GoM shelf resource available in 1989. Expect natural gas volumes to grow but prices to remain capped by coal through the mid-2020s.

Strategies

For upstream companies, the not-so-long grind through the early 2020s calls for a conservative approach to strengthen balance sheets, sustain dividend payments and drill within cash flows. Prices will be volatile and excessive exuberance will be punished by periods of low prices. However, it will be important to see around corners and monitor closely the factors that could shift the outlook to a new run-up in prices, requiring an expansionary emphasis on capturing new resources and a greater tolerance for debt.

The oilfield services sector has been hammered by the downturn and will likely consolidate further. It remains to be seen whether the consolidation will be lateral or vertical. Halliburton failed in its attempt to strengthen its verticals by merging with Baker Hughes; Schlumberger and Technip have taken a French solution of lateral extension by acquiring Cameron and FMC Technologies, respectively, and the forthcoming merger between GE Oil & Gas with Baker Hughes is also mainly lateral extension of business lines. Historically, oil companies have preferred to purchase equipment and services from best-in-class providers, and the new conglomerates will need to work hard to overcome past preferences and create a persuasive value proposition for bundling purchases of equipment and services from a single vendor.

Midstream companies should be able to resume organic growth as companies “replumb” energy infrastructure, aided by a supportive rather than hostile federal government and underwritten by producers seeking access to liquid markets.

Refiners and petrochemicals companies should benefit from an increasing gap between natural gas (used as feedstock and energy) prices and crude oil (setting international petroleum and petrochemicals products prices) as the oil price cycle will be out of phase with the gas price cycle. Nevertheless, these sectors will see limited volume growth and should continue to focus on limited capital improvements, operations excellence and accretive, synergistic acquisitions.

Well managed companies created value for shareholders through the 1990s by leveraging new technologies, simplifying their organizations to improve productivity, partnering creatively with providers of equipment and services and making acquisitions when prices were low. That playbook should be dusted off and updated for the next five years.

As a consultant, Professor and Energy Fellow Chris Ross works with senior oil and gas executives to develop and implement value creating strategies. His work has covered all stages in the oil and gas value chain.

UH Energy is the University of Houston’s hub for energy education, research and technology incubation, working to shape the energy future and forge new business approaches in the energy industry.